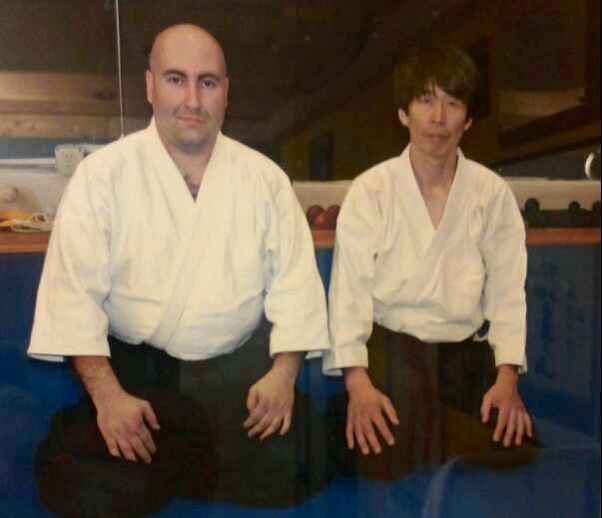

After starting Shotokan Karate and judo at a young age, John Araujo found aikido, feeling that it was time to explore this new art. He trained in traditional aikido for a decade until he sought out something more. Araujo searched and found Luis Santos in Florida. After participating in a grueling initiation and relearning process, he zealously learned all the aspects of Tenshin Aikido. Araujo continues to teach Tenshin Aikido in his Aikido of Bristol County, incorporating his previous martial experiences. Today, Araujo took some time to talk about the Tenshin Aikido community, its approach to training, and how traditional aikido can adapt to the changing martial landscape in the United States. All images provided by John Araujo.

Martial Arts of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: Welcome Araujo Sensei! Thank you for joining us today!

John Araujo: Thank you for having me here.

MAYTT: What was it about aikido that made you want to try it?

JA: I started martial arts around five or six years old; I was doing Shotokan Karate and judo. I watched aikido one time, and I thought it was unique; it was different, and I wanted to give it a shot. I thought it was pretty cool at that young age. I thought, at that point, it was time to start aikido.

MAYTT: Was there anything that aikido offered that your previous karate and judo training did not?

JA: I wanted to try something new with karate, particularly focusing on full-contact fighting, both offense and defense. However, I found myself drawn to aikido after also practicing judo. Aikido’s emphasis on redirection rather than direct conflict intrigued me. Unlike the intense physicality of karate, aikido seemed less about getting beat up and more about finesse. Yet, my initial experiences were humbling; being thrown around felt brutal compared to what I was accustomed to. Despite thinking I was conditioned from karate, aikido revealed a new level of physical demand, especially in terms of cardio and movement. Adapting to aikido’s unique stances and footwork, known as tai sabaki/ashi sabaki, proved to be a significant learning curve. I had anticipated an easier transition, but instead found myself embarking on a journey of relearning and refining my martial arts skills.

MAYTT: What continues to motivate you to train aikido today?

JA: When I started aikido at a young age, I was drawn to its focus on self-defense. However, in the first few months, I struggled to make progress. I considered quitting, but the supportive camaraderie of the community encouraged me to persevere. Fellow practitioners helped me address my weaknesses, fostering a desire to continue. I saw aikido as beneficial for my aspirations in law enforcement, where hands-on skills and self-defense proficiency were valuable, rather than aggression.

MAYTT: How would you describe the training you experienced when you first started aikido?

JA: When I first began practicing aikido, I noticed the emphasis on circular motion. Initially, under my original sensei, there was a unique approach: for the first six months, we focused solely on ukemi, the art of falling and rolling. I spent time perfecting forward rolls and assisting senior practitioners with theirs. Only after mastering ukemi did we delve into techniques. The repetition and movement in aikido were unlike anything I had experienced in Judo. While judo introduced me to ukemi and throws, aikido’s techniques were distinct. Gradually, aikido became more practical for me, particularly in the early 1990s when I found it truly remarkable. However, exploring different styles later on expanded my perspective dramatically, revealing gaps in my preparedness and broadening my understanding of martial arts.

MAYTT: That new style was essentially Tenshin Aikido. How did you come to find Tenshin Aikido? What inspired or influenced you to seek out Tenshin Aikido?

JA: When Above the Law starring Steven Seagal was released, I was already deeply involved in practicing aikido. Despite attending numerous seminars with esteemed senseis such as Yoshimitsu Yamada, Mitsunari Kanai, Kazuo Chiba, and Mitsugi Saotome, I couldn’t help but notice the stark contrast between the aikido portrayed in the movie and what I had been learning. Movie depictions often lack realism, but the aikido demonstrated seemed particularly different from what I knew, especially regarding techniques like shiho nages and irimi nage. Intrigued, I conducted research online and discovered a shihan in Florida whose teachings resonated with me. Transitioning to this new style marked a shift after approximately ten years of training in the traditional Aikikai style. While I’m uncertain if your current practice aligns with this, I remained within the Aikikai for a decade. With Steven Seagal’s active involvement in aikido, I eagerly signed up for a seminar in Montana, only to have it canceled due to his busy schedule. Nevertheless, I eventually found an opportunity to attend a seminar hosted by one of his students in Florida.

MAYTT: How would you compare the training you experienced with Tenshin Aikido to what you previously did with Aikikai/traditional aikido?

JA: It was undeniably brutal. That’s the word that kept resonating in my mind. As I searched for someone practicing Tenshin Aikido, the name Luis Santos surfaced. He was actively involved in the Tenshin circle, though the options were somewhat limited. Other names that emerged were George Angulo and Haruo Matsuoka Sensei, the latter of whom was heavily engaged in the LA District. Additionally, Craig Dunn Sensei was mentioned, yet he resided in Taos, New Mexico.

During my first seminar in Florida, I met a guy named Luis Santos. As the seminar began, we dove straight into warm-ups, which lasted around fifteen or twenty minutes before transitioning into ukemi. The ukemi portion was particularly intense; the rolls were tighter, the circles smaller. Initially, I couldn’t fathom why ukemi felt so different here. However, as I found myself taking ukemi for some of the other attendees, I soon realized they weren’t holding back. At that moment, I felt like an outsider, as if I were the black sheep enduring a relentless barrage.

As I discovered the reason behind the tight ukemi during practice, it became evident that the techniques emphasized smaller circles and precision. There was little room for error, especially when taking falls from high-quality practitioners. Unlike what I was accustomed to after over a decade of aikido training, where there was more time to prepare for a fall, here, it was immediate. Despite my years of experience, I found myself unprepared, resulting in sloppy falls and a sense of embarrassment akin to that of a beginner. However, over time, I was welcomed into the group. What also struck me was the emphasis on deflections, something entirely new to me. Techniques like suriage, which involved deflecting and redirecting attacks, were reminiscent of movements with a sword, a connection I hadn’t realized until then. It was a whole new dimension, especially when applied in randori practice.

During the first seminar I attended, towards the end of the class, we engaged in randori. However, this randori was unlike anything I had experienced in traditional Aikikai or general aikido practices. Every time I attempted to defend myself, I was swiftly knocked down. It felt as though I had no chance against my partners, who attacked with the force of football players. I found myself on the ground, unable to get up as they continued their assault. Despite the constant defeat, I found myself drawn to this intense style of practice. It was challenging, yes, but I couldn’t deny that I loved it. I realized then that I needed to delve deeper into this approach. It felt more practical, more attuned to real-world situations.

MAYTT: Talk about trial by fire.

JA: At that time, Tenshin Aikido felt like the ultimate choice for me. I had always thought aikido was just aikido, assuming there wasn’t much variation in styles available locally, and even now, Tenshin Aikido remains relatively obscure. It’s not widely advertised, often confined to small or private schools. Initially, I was told there’s no distinct style within aikido. However, I soon realized that different approaches existed, such as Iwama style, Yoshinkan Aikido, and Ki Society, each with its own techniques and philosophies. Despite this, some practitioners of Tenshin Aikido insisted it wasn’t a separate style but rather a name derived from Steven Seagal Sensei’s former dojo in Osaka, Japan, known as the Tenshin Dojo. When Seagal Sensei brought this approach to the United States, it became known as Tenshin Aikido. While some argue there’s no distinction, comparing Tenshin Aikido to the more traditional Aikikai style reveals differences in technique and approach. It’s worth noting that Seagal Sensei didn’t establish his aikido dojo in California as commonly thought; instead, he began in Taos, NM, under Sensei Craig Dunn before bringing Matsuoka Sensei to Los Angeles.

MAYTT: Thank you for that clarification. Were there any similarities between your previous aikido training and Tenshin Aikido or did you have to start from the ground up again?

JA: So, you’re familiar with the traditional aikido techniques, right? Like ikkyo, nikyo, sankyo, yonkyo, and gokyo? You might recognize the forms, but the way we apply them in Tenshin Aikido is quite different. Our approach focuses on tighter, more direct movements. For instance, when executing tenkan, the circular motion isn’t as expansive as what you might be used to. It’s more condensed and precise. Similarly, techniques like irimi nage involve a more direct approach, with less emphasis on large sweeping motions. In Tenshin Aikido, there’s no room for uke to adjust their position for a choreographed fall like in some other styles. The technique demands immediate response and adaptation, leaving no time for elaborate setups or adjustments.

Yeah, at that point, when I was finally accepted into that circle, I felt the need to prove myself. I had to show that I was worthy and committed to this path. So, I continued making trips back and forth to Florida, attending seminars and seeking guidance. I reached out to my shihan, who eventually became my mentor, inviting him to host seminars at my own dojo. Eventually, he took me under his wing personally, recognizing the need to refine my skills from the ground up. While I had a solid foundation in aspects like ashi sabaki and tai sabaki, there was still much to improve in terms of body movement and hand positioning. Despite years of aikido practice, the transition to this new style required a fresh perspective and dedicated effort. The principles remained the same, but the application shifted, especially in terms of deflections, which drew parallels to sword work.

It’s fascinating how Tenshin Aikido echoes the techniques of old Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu and Aikijujutsu. Before fully immersing myself in Tenshin Aikido, I had the chance to watch a few demonstrations of Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu on Aikido Journal. The similarities between the two were striking, prompting me to delve deeper into this connection. Many of the principles and techniques from Daito-ryu seemed to seamlessly translate into Tenshin Aikido applications. Additionally, having cross-trained in Japanese jujitsu, I found that incorporating techniques from my jujitsu background into my aikido practice proved highly beneficial.

MAYTT: You are expanding on what was already handed down to you.

JA: In recent years, aikido seems to have garnered a somewhat negative reputation, especially with the rise of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, MMA, and UFC. However, I believe aikido is suitable for everyone, but not everyone may be suited for aikido. When someone enters my Dojo, it’s often because they’ve been intrigued by aikido, whether through research or online exposure, and they want to give it a try. It’s beneficial if a beginner in aikido has some background in another martial art, as it can help them better appreciate the unique aspects of aikido. Aikido requires authenticity; if you can’t make it work realistically, you’re misleading your students. While there are indeed choreographed movements in aikido, as with any martial art, such as judo, karate, or jiu-jitsu, these are essential for learning and improving techniques. However, it’s crucial for aikido schools to pressure test their techniques to ensure effectiveness. Watching O-Sensei’s videos, it’s evident that his ukes attacked him with full force, and yet he effortlessly executed his techniques. While not everyone can reach that level, it’s still essential to pressure test your martial art to ensure its practicality and effectiveness.

As I mentioned, aikido has received its fair share of criticism, and at times, it’s fallen out of favor. People often say it only works on the drunk or in specific situations. But you can’t judge it until you’ve tried it. I have a deep respect for all martial arts; each has its place and purpose. Aikido, like any discipline, has its strengths and weaknesses. The key is to identify those weaknesses and work on strengthening them. Sometimes, it’s a matter of not fully understanding how to apply the techniques. It’s essential to challenge yourself and be open to cross-training. If you come into aikido with a background in another martial art, it can make the learning process smoother and more understandable. I’m fully committed to aikido, but I also recognize the value in exploring other disciplines.

I’ve also had the privilege of learning aikido from another instructor, Bruce Bookman, who is truly remarkable. He brings a diverse martial arts background, having trained in boxing and jujitsu, where he holds rankings. In addition to aikido, he teaches these disciplines. While I don’t offer separate jujitsu classes or hold any rankings in it myself, I’ve integrated principles from my cross-training experiences into my aikido teachings. For instance, I address scenarios where aikido techniques might not be effective, such as being taken to the ground. In these situations, I incorporate groundwork, including wrist locks and chokes, to enhance the effectiveness of our practice. Even during dan rank tests, I emphasize the importance of adaptability by challenging students to respond to various attacks and escape attempts, urging them to apply techniques such as arm bars, chokes, kimuras, or triangle chokes to neutralize the threat. This approach aims to refine our aikido practice and prepare students for real-world scenarios where versatility and quick thinking are crucial.

MAYTT: You mentioned previously about pressure testing. How have you pressure tested your aikido and what have you learned from that?

JA: In traditional aikido, when dealing with strikes like tsuki, the common approach involves executing techniques like tenkan to redirect the attack and then applying joint locks or throws, such as kote gaeshi. However, a noticeable difference in our practice is how we handle strikes. Instead of leaving our punches extended after striking, we retract them immediately. For example, if we throw a punch to the face or execute a jab, we swiftly bring our hand back rather than leaving it exposed for the opponent to grab. This fundamental difference affects our deflections and subsequent techniques. During practice, I evaluate the effectiveness of our techniques by simulating realistic scenarios. For instance, I may instruct uke to resist being thrown or to counterattack after the initial deflection. This pressure testing allows us to assess the practicality of our techniques and refine our responses accordingly. If a technique proves ineffective, I encourage exploration and adaptation, prompting students to adjust their approach and attempt to regain control of the situation. Through this process of trial and analysis, we aim to develop techniques that are reliable and adaptable in real-world encounters.

MAYTT: I see. While you were making the switch from traditional aikido to Tenshin Aikido. How did you students take to learning a new style and approach to aikido?

JA: That’s a great question. When I introduced the concept of pressure testing to my students, some of them were enthusiastic and eager to try it out, while others, approximately thirty percent, decided to leave. In my experience teaching seminars in traditional aikido, I’ve observed a similar pattern. Attendees often hope to encounter something new and stimulating during these events, as many seminars tend to cover the same basic techniques repeatedly. Despite the variety of applications possible, instructors often teach these techniques in a standardized manner, perpetuating a cycle of repetition within the aikido community.

I attended several seminars focused on traditional aikido, where I introduced alternative approaches to training. However, I encountered resistance, particularly from higher-ranked practitioners who were hesitant to embrace change. Despite demonstrating that the techniques could be executed safely and at varying speeds, some individuals were resistant to depart from their long-established methods. It seemed that many attendees were reluctant to deviate from their accustomed practices, perhaps out of fear of change or simply a lack of willingness to explore new possibilities. This resistance was evident even when introducing techniques such as chokes or incorporating kicking combinations, which are often overlooked in traditional aikido seminars. Unfortunately, my efforts to introduce these innovations were met with limited enthusiasm, and I often found myself not being invited back to lead future seminars.

Regarding my students, around thirty percent of them chose to leave because they were comfortable with the traditional approach and were resistant to change. However, I recognized the need to enhance the practicality of aikido, which led me to explore cross-training in jujitsu and eventually transition to Tenshin Aikido. While losing some students, I also gained new ones who were receptive to this shift. Overall, I believe it was a positive transition, and I’ve been committed to it ever since.

MAYTT: What was the Tenshin Aikido community like when you first joined here in the United States?

JA: Originally, Tenshin Aikido was somewhat isolated, primarily under the guidance of notable shihans like Larry Reynosa, who was renowned for his expertise in the art. Another remarkable figure was Lenny Sly, who also transitioned from the Saotome group to Tenshin Aikido through Larry Reynosa’s influence. Alongside them were individuals like Craig Dunn, Garrit Green, and Matsuoka Sensei, forming a tight-knit community. The atmosphere surrounding Tenshin Aikido at that time was almost secretive, akin to being part of an exclusive circle, owing in part to Steven Seagal’s involvement and the desire to safeguard the integrity of his aikido amid his rise to fame in the movies. Unfortunately, when Seagal departed and pursued his career in Hollywood, the community fragmented, leading to a decline in Tenshin Aikido’s prominence. Despite its diminished size, Tenshin Aikido remains a formidable and valuable martial art tradition.

Under the tutelage of Luis Santos, I underwent extensive training in Tenshin Aikido. His expertise and teachings significantly broadened my understanding of the art. However, gaining acceptance into his circle was not a simple matter; it required dedication and commitment. Unlike joining a typical aikido dojo, becoming part of Luis Santos’ group was more selective and exclusive. When I first encountered Tenshin Aikido and met Luis Santos, I had to prove myself worthy of inclusion. This journey wasn’t without its challenges, but my passion for the art drove me to persevere. Despite investing considerable time and resources into my training with him, our relationship eventually soured due to differences in our visions for aikido’s direction and teaching methods. As a result, we parted ways, each pursuing our own paths within the martial arts community.

Another remarkable shihan, Elliot Freeman, has been associated with Seagal for nearly 30 years. I’ve had the privilege of training with him and attending seminars at his school on multiple occasions. He’s also visited my school, demonstrating a close relationship with Seagal that persists to this day.

Referring back to your question, the Tenshin Aikido community was a very tight-knit one. There was a notion of what some called the “Tenshin curse,” where practitioners would engage with Tenshin Aikido for a while, only to disappear from the scene entirely. Many would remark, “Oh, whatever happened to that person who was into Tenshin Aikido?” It seemed like a common occurrence, though the reasons behind it remain unclear. Perhaps some practitioners were drawn to Seagal’s association and then lost interest, or maybe negative perceptions surrounding Seagal’s personal life played a role. As for myself, gaining acceptance into this community wasn’t as simple as expressing interest and starting training; it required immersion and acceptance into a tight circle.

MAYTT: You have already mentioned a few high-level shihan, but who do you feel would be the most influential in spreading and disseminating Tenshin Aikido here in the United States?

JA: My all-time favorite practitioners of Tenshin Aikido are Haruo Matsuoka Sensei and another individual, whose name I didn’t mention. Matsuoka Sensei, based in Culver City and Irvine, California, embodies incredible skill and embodies incredible skill and grace in his practice. Alongside his group of practitioners, including individuals like Josh Gold, Matsuoka creates an environment that’s both welcoming and inspiring. Despite his soft-spoken nature, his aikido techniques are incredibly powerful. It’s worth noting that Matsuoka Sensei further honed his skills by training under Abe Sensei in Japan after parting ways with Seagal. This additional training only elevated his mastery of Tenshin Aikido to new heights.

Craig Dunn Sensei and Matsuoka Sensei stand out to me as top-notch practitioners of Tenshin Aikido. Their extensive experience training alongside Seagal for over twenty years has undoubtedly contributed to their exceptional skill. Having personally trained at Craig Dunn’s Kihon Dojo in Taos, New Mexico, I can attest to his excellence in teaching fundamental techniques. Both Dunn Sensei and Matsuoka Sensei embody the essence of Tenshin Aikido, making them standout choices in my opinion.

MAYTT: In your Tenshin Aikido practice, do you feel that it has created both positive and negative perceptions and expectations from both practitioners inside and outside of aikido?

JA: Certainly, Tenshin Aikido presents a unique landscape, particularly in terms of instructor lineage. While some directly trained under Seagal Sensei, others are disciples of his first and second-generation students. From my observations and understanding, the challenge arises with certain instructors within Tenshin Aikido. While most are undoubtedly skilled and commendable, a few tend to critique fellow Tenshin practitioners. These dynamics are evident, especially when exploring various resources like YouTube or social media, where one can observe differing perspectives and teaching styles among instructors.

I consider myself both an aikido practitioner and student, encompassing the broader spectrum of aikido despite my focus on Tenshin Aikido. While I refrain from naming individuals, I’ve encountered a select few instructors who engage in critiquing others. In interviews, they may discredit practitioners by implying they haven’t trained with the best or aren’t genuine in their practice. This tendency isn’t unique to aikido; similar dynamics exist in other martial arts like jujitsu or karate. Personally, I disagree with such assertions.

If you’re interested in pursuing Tenshin Aikido, which is taught in very few dojos, I suggest reaching out to the instructor via email. It’s helpful to gather some background information and perhaps visit the dojo to see if it aligns with your goals. In my opinion, all martial arts should welcome those eager to learn. During my own journey, I encountered a tough environment at one dojo, akin to the military. Regardless of one’s experience or background, entry seemed restricted unless all criteria were met, which I found unfortunate. However, I persisted and eventually succeeded.

In the Tenshin Aikido circle, there’s a dynamic where first-generation practitioners, those who directly studied under Seagal, and instructors trained by Seagal often critique each other. This tension creates division, with some instructors forming close-knit groups while others engage in rivalry and comparisons of skill. It’s disheartening to witness this discord among talented individuals who excel in their craft. Ideally, students could benefit from the diverse teachings of all these instructors, as each offers unique insights and approaches.

Yamada Sensei, Kanai Sensei, Chiba Sensei, Seiichi Sagano Sensei, and Donovan Waite have all passed away. Each of them brought a unique perspective to aikido, reflecting their individual training and experiences. Despite their differences, they were all masters trained under the founder and offered valuable insights into the art. In Tenshin Aikido, there’s a diversity of approaches that can sometimes lead to tension or feelings of threat. Personally, encountering differences in vision and experiencing political issues led me to leave the aiki community and pursue my own path.

MAYTT: I want to use the word drama, but it sounds like there is a lot of drama in the Tenshin Aikido community.

JA: You’re absolutely right. It was indeed terrible. There’s just too much drama. Personally, I’m not a fan of it. I run my dojo very selectively, with a small group of people that I’m content with. We managed to pull through the pandemic without resorting to Zoom or online classes; we simply kept the dojo going with the students who maintained their memberships. Drama just doesn’t have a place in the dojo – it really doesn’t work out. On the other hand, organizations like Aikikai thrive because they stick together, functioning like a big, family-oriented group. While there may be rules in place, like not crossing over from one organization to another, the Aikikai world is vast and welcoming. I often encourage my students to attend seminars, even if they’re not Tenshin Aikido, to learn from different instructors. Personally, I’m not tied to any specific organization anymore. I’ve been part of the United States Aikido Federation and Aikido Schools of Ueshiba in the past, and even Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in Tokyo, Japan. Now, I’ve formed my own independent association and have the freedom to train with anyone I choose, and I extend the same freedom to my students.

MAYTT: It sounds like you are trying to embody that idea of: “Let’s all learn from everyone.”

JA: Absolutely, it’s a prevalent issue. Many individuals, not just with Craig Dunn, Reynosa, or Matsuoka, but also others closely tied to Seagal, remain in this sort of Seagal dream team mindset. They’re reluctant to venture outside because they perceive themselves as superior to others. While it’s understandable to feel that way, I believe people should explore and see what’s out there. Personally, I regularly inform my students about upcoming seminars in the area, encouraging them to attend. I’ve even invited jujitsu practitioners to cross-train with us, mixing black belts with white belts for joint training sessions. Collaboration and learning together should be the focus, rather than getting caught up in drama or comparisons of skill. It’s crucial to stop misleading students with false promises of magical techniques that defy reality. While there is internal power, such as core strength in jujitsu or centering in aikido, it doesn’t manifest as portrayed in some YouTube videos. It’s concerning when individuals with large followings propagate such unrealistic notions. Ultimately, relying on such illusions won’t help in real-life situations, like a potential confrontation at a gas station.

MAYTT: How has your interpretation of Tenshin Aikido, given your diverse background, expanded on what Seagal and your teachers have passed onto you?

JA: With my Tenshin background, I’ve developed my own curriculum and testing requirements. While I still incorporate traditional aikido into my teachings, I offer different interpretations based on my understanding of Tenshin Aikido. This allows me to demonstrate techniques from both perspectives, emphasizing variations and applications unique to each style. For instance, during a training session, I may focus on yokomen uchi kote gaeshi for an extended period, showcasing how it’s practiced in both traditional and Tenshin Aikido. By exploring hand transitions, uke nagashi, and suriage, I aim to broaden my students’ understanding and adaptability. This approach enables them to seamlessly blend into various seminars and environments, equipped with a versatile skill set. My students appreciate this flexibility and find it beneficial in their aikido journey.

MAYTT: It sounds like there is some validity in learning traditional aikido alongside Tenshin Aikido – that there is a place for traditional aikido.

JA: Absolutely, without a doubt. Many individuals initially practiced traditional Aikido but later sought out Tenshin Aikido, perhaps due to relocation or other reasons. I myself underwent this transition, and it wasn’t necessarily a dramatic change unless you wanted it to be. Both styles offer ample opportunities for learning and growth, whether transitioning from traditional to Tenshin or vice versa. Interestingly, I’ve observed that practitioners from the Iwama lineage adapt particularly well and quickly to this transition, displaying openness and readiness for new experiences.

MAYTT: Is it the way that Iwama approaches everything?

JA: Yes, indeed. The Iwama approach often appears more structured, almost robotic, compared to traditional aikido. However, I’ve trained extensively with practitioners from the Iwama lineage, and I must say, they excel at transitioning between styles. Their adaptability and openness are truly impressive. I have great admiration for them and also for my own students, who demonstrate similar qualities.

MAYTT: Which style have you seen having the most difficult time transitioning to learn Tenshin Aikido?

JA: The practitioners from traditional aikido backgrounds, such as those in Yamada Sensei’s and Kanai Sensei’s groups, often struggle with change. My original instructor, who was affiliated with the United States Aikido Federation, a blend of Yamada and Kanai Senseis’ teachings, instilled this mindset in me. I’ve noticed that individuals from these groups tend to be rigid in their approach and find it challenging to adapt. However, there are exceptions. For instance, during a seminar in Florida a few years back, Hayato Osawa demonstrated remarkable versatility. While executing a yokomen uchi shiho nage, he smoothly transitioned into an uke nagashi when the attacker unexpectedly accelerated. Despite their proficiency in these techniques, many older-generation aikido masters seldom emphasize them in their teachings. Although such instances are documented on video platforms like YouTube, they often go unnoticed by practitioners focused solely on traditional techniques. Witnessing Osawa Sensei’s swift reaction was enlightening, prompting me to rewatch and analyze the sequence repeatedly.

Absolutely, there’s a balance between preserving tradition and evolving aikido to attract more interest. While the Ueshiba family and the current Doshu may prioritize maintaining O-Sensei’s teachings, there’s a need for revitalization within aikido. Personally, I believe that aikido must adapt to remain relevant and appealing to a wider audience. While practitioners like us may always have an interest in aikido, attracting younger generations is essential for its longevity. In my experience, some aikido techniques seem impractical in real-world scenarios, which underscores the need for innovation. While aikido typically avoids visible injuries, my dojo embraces realistic training, acknowledging that bruises, blood, and even broken bones may occur during practice. This approach ensures that my students understand the practical applications of aikido techniques.

MAYTT: Besides having younger students coming in, what other aspects of aikido need to be revamped or redone to gain more interest?

JA: The entire aikido system requires a significant boost, which must originate from Doshu in Japan, particularly from the Aikikai main headquarters. While O-Sensei himself delved into jujitsu, the evolution and adaptation of Aikido techniques should be emphasized more. Currently, when observing Doshu, the repetition of the same techniques is evident, which may not reflect real-world scenarios accurately. Drawing from my law enforcement background, I can attest that attacks seldom resemble those demonstrated in traditional aikido settings. It’s time for a reevaluation, especially among the younger generation of Aikikai practitioners who are poised to assume leadership roles. Acknowledging criticisms about aikido’s impracticality and its portrayal in movies, there should be a concerted effort to pressure test aikido techniques and make necessary adjustments to align with real-world self-defense needs.

I’ve observed Tomiki Aikido, and it strikes me as quite different, even a bit odd. However, they incorporate competitions into their practice, which is unusual for aikido. I understand that aikido wasn’t originally designed to be competitive, as its roots lie in combat techniques for samurai. Yet, there’s a necessity for aikido to evolve and improve to maintain interest. Jujitsu’s effectiveness is well-established, which explains its popularity.

Seagal undoubtedly elevated aikido’s profile through his movies, but I’m aware that much of what we see on screen doesn’t translate to real-world self-defense scenarios. I emphasize to my students that our techniques and falls in the dojo won’t necessarily play out the same way on the streets. That’s why we sometimes train outdoors, wearing sneakers and jackets, and incorporate sticks and bats instead of traditional weapons. I stress the importance of realism, reminding them that people they encounter outside the dojo won’t cooperate like training partners; they’ll resist, pull, and fight back. So, we prepare for that resistance here, allowing my students to adapt and respond effectively in real-life situations.

I believe aikido needs to evolve beyond its traditional basics. While there’s value in preserving tradition, embracing innovation can lead to a more effective practice. Many are seeking additional elements in their martial arts training, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Personally, I have a deep appreciation for traditional martial arts, but I think aikido could benefit from a revamp. When O-Sensei was alive, he didn’t engage in the kind of flashy, impractical techniques we often see today. The rise of no-touch aikido demonstrations on platforms like YouTube has tarnished aikido’s reputation. Such demonstrations are not reflective of the art’s true effectiveness.

MAYTT: It is annoying at times when someone brings up something like that.

JA: Absolutely, aikido was once effective and proven. For instance, there’s the story of a champion sumo wrestler who challenged O-Sensei and lost, eventually becoming his direct student. Additionally, several practitioners of judo and Japanese jujitsu were sent by their masters to learn aikido from O-Sensei. This indicates that aikido had validity and respect among martial arts circles. However, over time, aikido seems to have lost its effectiveness and relevance. It’s reminiscent of what happened with Bruce Lee’s martial arts philosophy, which was effective in its time but has been diluted over the years. Aikido should return to its roots and focus on the fundamentals that made it successful in the past. There needs to be a collective effort within the aikido community to address these issues and determine the direction forward.

MAYTT: I agree. Do you have anything else that you would like to say before finishing?

JA: Certainly, I believe that the new Doshu at the Aikikai headquarters should be more receptive to feedback from the current generation of practitioners. While I’ve distanced myself from aikido politics and organizations, I recognize the challenges of introducing change in a traditional Japanese environment. Nonetheless, I feel it’s essential for the leadership to acknowledge the concerns of practitioners worldwide. Many instructors have seen a decline in student numbers and have faced criticism regarding the effectiveness of aikido as a martial art or self-defense system. If these issues are not addressed, aikido’s popularity and relevance may continue to decline. It won’t be easy to reverse this trend, but with the right approach and collaboration, it’s achievable. The Aikikai headquarters, being one of the largest in the world, should take a proactive stance in addressing these challenges, especially considering the financial implications for dojos globally.

MAYTT: Thank you, Araujo Sensei, for this wonderful conversation!

JA: It was great being here!

To learn more about aikido and its history in America, click here.