During a time of anti-violent movements, George Ledyard stumbled upon an aikido demonstration while living in Washington DC. After watching the demonstration and talking with the leader of the group, Mitsugi Saotome, Ledyard was convinced to try out a class. From that moment, he was hooked. As the years went by, Ledyard trained in other martial arts to better his aiki, opened his Aikido Eastside in 1989, and has thought a great deal about the future of aikido. Today, Ledyard took some time to speak with us about those thoughts and his experiences. This interview is the first part of a two part interview. Read the second part here.

Martial Arts of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: Welcome Ledyard Sensei! Thank you for joining us today!

George Ledyard: Thank you for having me!

MAYTT: You began training with Mitsugi Saotome in Washington, DC in 1977 after studying karate in college. What was it about aikido that drew you to it and what continues to motivate you to sustain your training?

GL: What drew me to aikido was more than just the art itself; it was Saotome Sensei. Since childhood, I’d been captivated by martial arts, inspired by icons like Bruce Lee in The Green Hornet. My interest led me to dabble in karate during college, where I was fortunate to have a good instructor, though my experience only reached green belt level. Despite my limited skill, I was deeply impressed by the demeanor, focus, and projection of accomplished martial artists.

During my time at Cornell University, witnessing Hidetaka Nishiyama’s karate demo further solidified my admiration for martial arts practitioners. Their presence, focus, and technical proficiency left a lasting impression on me. Later, while living in DC, a friend mentioned aikido and an exceptional instructor who had recently arrived in town. However, it wasn’t until stumbling upon a poster for a demo one evening in Georgetown that I took action.

Attending the demo, I was introduced to Saotome Sensei and five yudansha who had relocated to assist him in opening the DC dojo. Even though my understanding was limited as a novice, the demonstration was mesmerizing. It was evident that Saotome Sensei’s skill was exceptional, though I lacked the expertise to fully comprehend its depth at the time.

Intrigued by what I had witnessed, I wasted no time in joining the dojo. Within weeks, I found myself training diligently, often six or seven days a week. Now, forty-seven years later, I’m still here, deeply committed to aikido and grateful for the journey it has taken me on.

MAYTT: What was it about Saotome Sensei that caught your eye and wanted to learn directly from him?

GL: When I finally got a chance to talk to him, it was after I went to the dojo for the demo. The demo itself was incredibly captivating. Though it’s been so long now that I can’t recall the specifics, I likely conversed with some of the black belts who were eager to recruit new members. They must have encouraged me to join the dojo, though the details escape me. What I do remember vividly is my first night on the mat.

Walking into the dojo, I was greeted by a group of black belts training under Sensei. There was no separate beginner class or special accommodations. Someone kindly stepped off the mat to provide me with a gi and showed me how to tie my obi and bow properly. I was then ushered onto the mat, where I dove headfirst into the aikido experience.

Reflecting on my beginner experience, I often describe it as being thrown into the deep end. The very first technique I attempted was yokomen uchi shiho nage ura. I followed along as best I could, learning through trial and error. The feedback was direct and immediate: Bam! “It would be better if you tucked your chin, so your head didn’t hit the mat.” Bam! “It would be better if you tucked your foot behind the other.” There was no easing into it; I simply joined in and learned as I went.

I cherished every moment of my training, but it was a serious endeavor back then. The individuals who populated the dojo were deeply committed, and among them were five yudansha who had relocated from various parts of the country, including Raso Hultgren Sensei, who now serves as the chief instructor in Missoula. One of my initial instructors was Hultgren Sensei, and her dedication was emblematic of the atmosphere in the dojo.

Almost everyone trained daily, with few exceptions. I believe I was one of the few who were married, and even among the dedicated practitioners, most held jobs solely to support their training. There was little focus on conventional career paths; rather, the priority was earning enough to sustain oneself and continue training. Personally, I was employed at Eddie Bauer’s retail store at the time, a job that provided me the means to pursue my passion for aikido.

After each class, a ritual emerged: while we weren’t permitted to socialize in our gis, Sensei was strict about that, so the gis came off and the beers came out. A couch against the wall beside the mat served as our gathering spot. For about an hour post-class, we’d engage in discussions about aikido, sharing insights and experiences. It was during these conversations that I realized the depth of Saotome Sensei’s wisdom. His understanding of aikido far surpassed our own, yet his willingness to share his knowledge with us was profound. It was then that I knew I had stumbled upon something truly exceptional – Saotome Sensei was indeed the real deal.

Saotome Sensei shared a close bond with O-Sensei, stemming from his early days as a young student, a common experience for many in the aftermath of the war. His relationship with O-Sensei was familial in nature; the elder masters treated him like a grandson. Stories abound about the strictness of O-Sensei’s teaching, but beneath that discipline lay a deep connection between them. For me, aikido is intimately intertwined with O-Sensei’s legacy.

In contemporary discussions within the aikido community, there’s often a quest to reconnect with O-Sensei’s martial roots, especially as some practitioners explore Daito-ryu and delve into concepts like internal power. This shift towards technical proficiency is understandable given the complexities inherent in martial arts. However, there’s also a noticeable trend towards what might be termed “O-Sensei worship.”

While it’s crucial to address technical aspects and refine our understanding of aikido’s martial applications, I believe there’s a danger in idealizing O-Sensei to the point of mythologizing him. It’s essential to honor his teachings and legacy, but we must also recognize the human dimension of his practice and the evolution of aikido beyond his era.

As aikido gained momentum, it was the tail end of the hippie era, marked by a prevalent ethos of peace, love, and harmony. In this atmosphere, individuals projected their ideals onto the art, shaping it according to their own aspirations. Throughout my journey, I’ve been fortunate to have a teacher who spent fifteen years with O-Sensei. His insights provided me with a profound understanding of O-Sensei’s teachings, offering a glimpse into the essence of the art.

However, delving deeper into O-Sensei’s legacy revealed the complexity of his character. Each teacher who trained under him gleaned something unique, resulting in a myriad of interpretations. With experience, I’ve come to appreciate the diversity of perspectives among those who studied alongside him. It’s fascinating to witness how different individuals extracted distinct lessons from the same source, highlighting the richness and depth of O-Sensei’s teachings.

I had numerous interactions with Kazuo Chiba Sensei, and I found him to be very respectful towards me. I attended his classes and engaged in conversations with him on several occasions. It was evident that his approach to aikido differed significantly from Saotome Sensei’s. Despite these differences, both Chiba Sensei and Saotome Sensei shared a deep reverence for O-Sensei and a commitment to preserving aikido as a genuine martial art rather than merely a form of movement. They both embodied the spirit of budo, yet their individual styles and perspectives were distinct.

In my dojo, I proudly display a picture that Saotome Sensei personally gave me. It captures O-Sensei teaching a class, likely taken about a year before his passing, around 1967 or 1968. In the photo, O-Sensei stands at the forefront, with Kisshomaru observing from the side, and the deshi lined up attentively. Notably, Saotome Sensei sits beside Chiba Sensei, both immersed in the same training environment, receiving the same instruction.

As I deepened my understanding and encountered more teachers over time, I came to appreciate the unique perspective that Saotome Sensei brought to his aikido. While it was evident that his teachings were influenced by his experiences, there was an undeniable authenticity to his approach. Unlike some accounts from individuals without direct experience, Saotome Sensei’s insights were rooted in genuine encounters with O-Sensei.

Reflecting on my journey in aikido, it was Saotome Sensei’s connection to O-Sensei that truly captivated me and kept me engaged in the practice. While I enjoyed training in other martial arts like karate, it was the profound connection between Saotome Sensei and O-Sensei that sparked my love for aikido.

Discovering someone of Saotome Sensei’s caliber was pivotal for me in my aikido journey. Truthfully, there are very few individuals I’ve encountered who possess the same level of sophistication in their practice. If it weren’t for encountering him as my initial aikido teacher, I might not have persisted in the art. Having observed numerous aikido practitioners over the years, I can confidently say that few have matched the depth of Saotome Sensei’s expertise.

When advising others on finding a suitable dojo, I emphasize the importance of finding a great teacher above all else. The quality of instruction ultimately determines the value one gains from practicing aikido. I’ve been asked countless times about how to go about finding a dojo, and my advice remains consistent: prioritize finding a teacher of exceptional skill, regardless of the martial art being taught. A great teacher will always surpass a mediocre one, regardless of the specific discipline.

Fortunately, luck has been on my side throughout my martial arts journey. From the outset, I’ve had the privilege of training under top-level instructors. Whether they were American or Japanese, every teacher I’ve encountered has been exceptionally skilled. This stroke of fortune has been consistent throughout my martial arts career, and I’m immensely grateful for the caliber of teachers I’ve had the opportunity to learn from.

MAYTT: That is amazing how you stumbled upon Saotome! Could you speak more to the O-Sensei worship when you started? And is O-Sensei worship still going strong in the twenty-first century?

GL: I believe that inherent inclinations remain relatively unchanged over the years. aikido, unlike karate, doesn’t adhere to a rigid, centuries-old set of techniques and transmission methods. Its dissemination has been rapid, particularly in the decades following World War II. In the 1960s, there was a noticeable surge in aikido’s popularity, and by the 1980s, its practitioners numbered in the millions worldwide.

Considering the time it takes to develop a well-qualified instructor – roughly a decade – aikido didn’t have sufficient time to produce a large cohort of highly skilled teachers. Many of the young deshi who trained in Japan during O-Sensei’s final years had already been dispatched overseas. Some had only five to six years of training at Hombu Dojo. Notably, many of the individuals who introduced aikido to America were relatively low-ranked, typically third or fourth dans, and not highly esteemed shihan.

Consequently, the range of exposure to high-level instruction in aikido has been quite broad. While some practitioners may have had significant mat time with instructors like Chiba Sensei or Saotome Sensei, many others have had limited exposure, perhaps attending seminars intermittently. For the majority, their training experience likely falls at a lower level of expertise.

MAYTT: How would you describe the training that you experienced under Saotome and in what ways have you seen such training change or evolve over the course of time?

GL: Each year, we attended camp, providing us with opportunities to interact with high-level instructors. However, for most practitioners, this exposure was sporadic. My experience, along with individuals like Bruce Bookman Sensei, who trained directly under Chiba Sensei in Japan, was unique. Bookman Sensei underwent intensive deshi training under Chiba Sensei’s guidance, a level of immersion that significantly impacted his development.

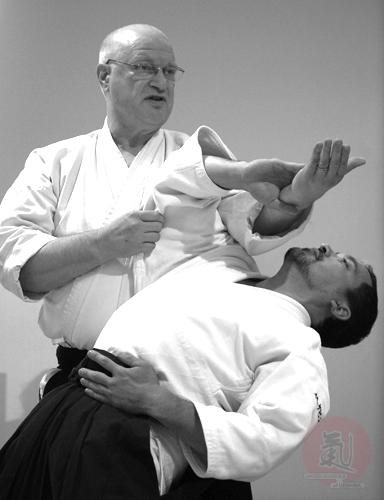

When I trained with Saotome Sensei, I vividly recall being a novice white belt thrown into the mix. Saotome Sensei made it clear from the outset: he was molding professional instructors. This intention permeated our training sessions, as Saotome Sensei poured his expertise into us with a singular focus. He aimed to cultivate a generation of Shihan, and our instruction reflected that goal. Every technique, every lesson was infused with the depth and intensity necessary to prepare us for that role.

As I observe the training experiences of most aikido practitioners, especially during my travels teaching seminars across the country and internationally before the lockdown, I often notice significant disparities. Despite individuals accumulating ten, fifteen, or even twenty years of aikido practice, their instructional backgrounds differ vastly from mine. This disparity extends beyond technical proficiency; it encompasses the entire breadth of their aikido education.

Reflecting on the era when I began practicing aikido, instructional resources were limited. Only a handful of books existed on the subject, and while some were inspirational, they suffered from poor translations. Discussions about internal power and the connection between aikido and aiki were virtually nonexistent. Although a few aikido practitioners dabbled in Chinese arts, bringing some awareness to these concepts, it was not widespread.

Over time, there has been a notable shift in the discourse surrounding aikido, with increased attention to topics like internal power and the influence of Chinese martial arts. However, it’s evident that the awareness of these concepts was minimal during the early stages of my aikido journey.

Many factors have contributed to the evolution of aikido over time, significantly altering the landscape of the art. One such factor was the wide range in the quality of instruction available. Despite this disparity, one common thread was the dedication and passion of those passing on the art. Across the country, dojos began to emerge, often in remote areas with sparse student populations. Despite the challenges, practitioners poured their hearts and resources into building these dojos, demonstrating a profound commitment to aikido.

Financial sacrifices were commonplace, with individuals investing every spare dime into constructing beautiful dojos and attending aikido camps. This fervor stemmed from a deep love for the art and a desire to immerse oneself fully in its practice. However, the varied quality of instruction available resulted in a diverse transmission of aikido principles and techniques. This diversity ultimately shaped the aikido landscape, contributing to its rich and multifaceted nature.

This diversity of instruction has led aikido to undergo something akin to an identity crisis. While individual teachers possess a clear understanding of their own practice and can articulate their methods and philosophies, there is a notable lack of consistency across the art as a whole. Even teachers with similar levels of experience may offer vastly different perspectives and approaches to the art.

This phenomenon is not confined to any one region; it’s evident both in the West and in Japan. Consider the stark contrast between traditionalists like Hiroshi Isoyama Sensei or Sadateru Arakawa Sensei, who epitomize the hardcore, old-school budo ethos, and figures like Nobuyuki Watanabe Sensei, known for his emphasis on esoteric concepts such as energy manipulation. It’s remarkable to ponder whether these diverse approaches can all trace their roots back to O-Sensei’s teachings.

The lack of a strict transmission method has allowed individual instructors to interpret and adapt aikido according to their own preferences and inclinations. As a result, the art has splintered into various interpretations and styles, to the extent that the practices of different teachers might seem like entirely different arts altogether.

During Stan Pranin’s tenure at Aikido Journal, I contributed an article questioning the very essence of Aikido. With each practitioner holding their own interpretation of what aikido entails, it raised the question: does a singular, definitive concept of aikido truly exist? My understanding of aikido is rooted in the teachings passed down to me by Saotome Sensei, shaping both my personal practice and my approach to teaching my own students.

My journey in aikido has been marked by a relentless pursuit of understanding and mastering aspects of Saotome Sensei’s teachings. However, there came a pivotal moment, likely after attending the first few Aiki Expos, where I encountered teachers who possessed insights that even Saotome Sensei couldn’t articulate. Their understanding seemed to transcend mere technical instruction, reflecting a holistic grasp of aikido’s essence.

While Saotome Sensei’s teachings laid a foundational framework, I realized that for many of us, including myself, additional guidance was necessary to unlock the deeper intricacies of the art. Even esteemed practitioners like Hiroshi Ikeda Sensei acknowledged the complexity of Saotome Sensei’s teachings, recognizing that it often took years to fully grasp the depth of his insights.

The Aiki Expos gave a lot of us exposure to some Daito-ryu and Aikijujutsu teachers; they exposed us to Tetsuzan Kuroda Sensei, the swordsman in Japan, and Kenji Ushiro Sensei, the karate teacher. They had different training methodologies and different ways of explaining things. In a number of our cases, all of a sudden, lights went on. In my case, I was training with these guys, and they would show me something and I would go, “Oh my God, that’s what. Sensei was doing. And I never got it.” Being able to look at aiki from varied viewpoints was really helpful.

I recognize that I’m nowhere near the level of Saotome Sensei, and I attribute this disparity partly to differences in training intensity and duration. During his time as a deshi in Japan, Saotome Sensei dedicated himself to rigorous training schedules, often spending six to eight hours on the mat every day, seven days a week. His training regimen included regular sessions with O-Sensei, Seigo Yamaguchi Sensei, Kisaburo Osawa Sensei, and others. Additionally, he was tasked with teaching classes at various company clubs and schools, including children’s classes.

Saotome Sensei’s immersive training experience far exceeded that of many practitioners, myself included. For those of us who didn’t have the opportunity to become uchi deshi in Japan, our training experiences differed significantly. While Saotome Sensei honed his skills through daily exposure to aikido luminaries and extensive teaching responsibilities, most practitioners outside of Japan had to balance their training with other commitments.

Saotome Sensei’s unparalleled dedication and immersion in aikido contributed to his exceptional skill and understanding of the art. While I strive to emulate his commitment and passion for aikido, I recognize that my training journey has followed a different path, one shaped by my own circumstances and opportunities.

Some individuals, like Kayla Feder and Mary Heiny Sensei, have undergone intense training experiences that mirror the immersion Saotome Sensei experienced in Japan. Kayla Feder trained in Iwama under Morihiro Saito Sensei, where rigorous daily sessions on the mat were the norm. Similarly, Mary Heiny Sensei spent time at both Hombu Dojo and later in Shingu, training extensively under Michio Hikitsuchi Sensei.

Osawa Sensei, who knew Mary Heiny from Hombu Dojo, once remarked that she was the toughest woman he had ever encountered, a sentiment that speaks volumes given his stature within the aikido community. He noted her exceptional dedication, recounting how she attended every class from early morning until late at night, a level of commitment that few could match.

These accounts serve as testaments to the rigorous training regimens undertaken by dedicated practitioners like Kayla Feder and Mary Heiny Sensei. Their unwavering commitment to aikido, demonstrated through countless hours on the mat, exemplifies the level of dedication required to truly excel in the art.

The level of hands-on mat time coupled with quality instruction is likely what sets the true masters apart from the rest of us in aikido. Despite my commitment to training seven days a week, my practice typically consisted of a few hours of class each night, supplemented by occasional seminars. However, aikido camps offered a unique opportunity for immersive training, resembling the intensity experienced by deshi in Japan.

Aikido camps, occurring annually for a week during the summer, provided a rare chance for practitioners like myself to engage in consecutive classes with various instructors. These intensive sessions were akin to the rigorous training regimen followed by deshi in Japan, where daily immersion in aikido was the norm. While such experiences were special occasions for us, they allowed for a deeper level of engagement with the art and its teachings.

I believe that the primary factor separating me from achieving what Saotome Sensei is capable of is simply practice. Over time, I’ve gained a deeper understanding of his refined techniques, particularly his skill in creating what I would describe as neutral space. Despite our physical differences – with me being twice his size, akin to a football player, while he’s a lean 135 pounds – Saotome Sensei’s ability to effortlessly maneuver is truly remarkable.

I vividly recall instances where I would apply what I thought was a powerful grab, only to find Saotome Sensei effortlessly evading it with a smile. His movements seemed effortless, almost as if he were simply flowing with the interaction. For many years, I struggled to comprehend the subtleties of his technique. While senior practitioners like myself attempted to emulate his abilities, it often felt elusive.

However, I never subscribed to the notion that his mastery was unattainable for others. Saotome Sensei himself often encouraged us by saying, “If I can do it, you can do it.” This belief fueled my determination to unravel the secrets behind his seemingly effortless movements.

During the Aiki Expo, I had a transformative experience while interacting with Tetsuzen Kuroda Sensei, a renowned swordsman with expertise in Aikijujutsu. Instead of focusing on specific techniques, he emphasized principles during his sessions. One particular exercise involved him allowing my partner to feel his arm, which appeared soft and relaxed. However, when he moved, I found myself unexpectedly on the floor, while my partner noted that Kuroda Sensei’s muscles hadn’t seemed to engage.

This moment was a revelation for me, occurring after decades of training. It sparked a realization that my understanding of aikido had been incomplete. I began questioning my assumptions about where power truly emanated from within the art. It became evident that the source of strength lay beyond mere muscular engagement.

This epiphany marked a significant turning point in my aikido journey. It was akin to a sudden illumination, akin to a Zen-like moment of clarity. From that point forward, my approach to aikido underwent a profound transformation, guided by newfound insights into the principles underlying the art’s effectiveness.

If you haven’t been training diligently and properly, attending seminars with highly skilled instructors can be a humbling experience. These experts operate at such a high level that even after spending an entire weekend immersed in their teachings, returning home and attempting to replicate their techniques can feel daunting and elusive. This challenge underscores the importance of laying a solid foundation through consistent and dedicated training.

I deeply appreciate the invaluable lessons I received from Saotome Sensei during our formative years. Back then, we were all young, in our twenties, and trained with an intensity bordering on fanaticism. Looking back, some of our training methods may have been overly strenuous, leading to physical wear and tear that persists into our seventies. However, this rigorous training regimen also provided us with a strong foundation.

Despite the toll it may have taken on our bodies, this intense training allowed us to develop the skills necessary to understand and emulate the techniques demonstrated by high-level instructors. While hindsight may reveal that we could have tempered our training intensity for long-term physical well-being, there’s no denying the invaluable groundwork it laid for our martial arts journey.

If you haven’t laid down that foundational groundwork, it becomes evident when you’re faced with advanced techniques. You can feel the depth of skill within reach yet struggle to access it. This highlights a significant issue: while the instruction is readily available, many practitioners aren’t training in a way that allows them to capitalize on it. I observe this trend persisting as the martial arts landscape evolves, particularly with the dominance of mixed martial arts and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

As our martial arts communities age, there’s a noticeable absence of younger individuals who possess both the desire and physical capability to undergo rigorous training. In my own dojo, it’s only recently that we’ve welcomed a few individuals in their twenties. Their presence has injected new energy, and some are progressing impressively. However, for a significant period, new students were often in their forties, already past the point where the strenuous training of our youth is advisable. Unlike in our twenties, where bumps and bruises healed swiftly, injuries at this age can linger and hinder recovery.

It’s crucial for practitioners to adapt their training approach to maximize the benefits of available instruction. Without a commitment to diligent and physically demanding training, accessing advanced techniques can remain elusive. As our community ages and evolves, it’s essential to cultivate an environment that welcomes individuals of all ages and supports their martial arts journey at every stage of life.

MAYTT: What are your views on cross training in other martial arts?

GL: I firmly believe in the value of cross training and seeking instruction from various teachers. If you’ve been under the guidance of one teacher for two or three decades, you’ve likely absorbed what they had to offer based on your readiness to receive it. However, exposing yourself to different perspectives can broaden your understanding and deepen your skills. It’s akin to the parable of the blind men and the elephant, where each perceives the elephant differently depending on which part they touch. Similarly, encountering diverse teachings allows for a more comprehensive grasp of the art.

I was fortunate in this regard because Saotome Sensei was remarkably secure in his abilities and didn’t view seeking instruction elsewhere as disloyalty. He understood that exposure to different teachings could enhance one’s aikido rather than detract from it. I made it clear to other teachers that my goal in cross-training, whether it was with Ellis Amdur Sensei or Howard Popkin Sensei, was to improve my aikido. Their generosity in allowing me to explore different paths while remaining dedicated to aikido was invaluable.

Training with various teachers had a transformative effect on my aikido practice. Each instructor brought unique insights and methodologies, enriching my understanding and skill set. Their generosity and willingness to share their expertise played a pivotal role in shaping my journey and contributing to the evolution of my aikido.

In the early 2000s, I noticed a significant shift in my aikido practice, and it began to yield tangible results. Similar to Saotome Sensei’s technique, my aikido began to work more effectively. One individual who played a crucial role in this transformation was Dan Harden. His guidance on internal power development was invaluable. His instructions were clear and methodical, offering a step-by-step approach that led to noticeable improvements. Moreover, his fluency in English facilitated understanding, enhancing the learning experience.

Throughout my training, I encountered instructors who possessed profound knowledge but struggled to articulate their teachings effectively. Language barriers often complicated the learning process. For instance, a Japanese instructor might use terms like “push” or “pull,” which, when translated, may not accurately convey their intended meaning. This linguistic ambiguity remains a challenge in aikido instruction, requiring students to navigate through potential misunderstandings.

Incorporating insights gained from cross training, I introduced new elements into my aikido practice. I aimed to expand rather than restrict the scope of the art, ensuring that my teaching encompassed a diverse range of techniques and principles. While some instructors may have resisted such diversification, I believe it is essential for the continued evolution of aikido. This approach has allowed me to cultivate a unique style of aikido, enriched by the integration of various influences.

I’ve endeavored to preserve the essence of what I learned from Saotome Sensei while allowing room for evolution in technique. Saotome Sensei himself encouraged us to explore, cross-train, and develop our unique expressions of aikido. Unlike practitioners of Iwama-ryu, who strive to adhere strictly to the teachings of Saito Sensei, I’ve embraced innovation and adaptation. My approach isn’t about replicating a past era; it’s about honoring the spirit of innovation that Saotome Sensei instilled in us.

One significant addition to my aikido practice is the incorporation of the two-sword technique. This innovation, pioneered by Saotome Sensei, represents a departure from traditional aikido teachings. Inspired by his curiosity about two-sword techniques found in certain Japanese koryu, Saotome Sensei sought guidance from O-Sensei. O-Sensei’s response, encouraging him to delve into the subject independently, exemplifies his philosophy of empowering students to explore and create within the art. Saotome Sensei’s pioneering spirit resonated with me, prompting me to delve deeply into this aspect of aikido and integrate it into my practice.

While remaining grounded in the principles passed down by Saotome Sensei, I’ve embraced innovation and exploration in my aikido journey. My goal is not to replicate the past but to honor its legacy while pushing the boundaries of the art and discovering new avenues for growth and expression.

In my teaching, I’ve introduced elements that I didn’t directly learn from Saotome Sensei. I make a conscious effort to acknowledge the sources of these additions, attributing them to instructors like Alexander Sensei, Popkin Sensei, and Don Angier, among others. However, after many years of practice, there are techniques and concepts that I’ve incorporated without always recalling their origins. Despite this, I remain committed to maintaining transparency and giving credit where it’s due in my teachings.

There’s still a wealth of sophisticated knowledge available within the aikido community, particularly regarding the integration of internal power principles. Certain instructors are actively working to enhance their aikido by incorporating these elements. One example is a sensei who demonstrates remarkable skill in neutralizing attacks effortlessly, despite appearing to make no visible movements. However, achieving this level of proficiency requires extensive foundational work and dedication to mastering these principles before one can fully appreciate and apply them.

MAYTT: Something that comes up a lot in aikido training is aiki. How would you find aiki in aikido training?

GL: It’s a challenging aspect to navigate. Much of aikido lacks genuine aiki, especially when viewed from the perspective of internal power or the principles of internal arts, as the Chinese would describe it. Instead, a significant portion of aikido relies heavily on external, physical techniques. While proficient physical aikido embodies the essence of aiki through movement, true aiki is distinct. Mastery of movement dynamics, such as understanding neutral pivot points or jiku in Japanese, and the application of power along weak angles can enhance technique effectiveness. However, this effectiveness doesn’t necessarily equate to genuine aiki.

I recall reading a statement, possibly from a Daito-ryu teacher, that resonated with me and applies well here. It suggested that if one fully comprehends what has been done to them during training, it likely wasn’t genuine aiki. This insight underscores the elusive and subtle nature of true aiki, which often transcends conventional understanding and defies straightforward explanation.

Encountering individuals with immense physical strength and power can be impressive, no doubt. I’ve trained with some who seemed unstoppable, possessing wrist locks like nikyo that could practically tear your wrist off if they wished. Their mastery of weight shifting, and hip power was remarkable. However, there’s a limit to relying solely on such physical prowess. This approach doesn’t necessarily lend itself to continual improvement over time.

Consider Yukiyoshi Sagawa, a contemporary of our teacher, Saotome Sensei. Sagawa once humorously remarked to me, “I didn’t start to get good until I was eighty and had my stroke.” It’s a poignant statement, suggesting that true mastery may come later in life, even amid physical challenges. Physical aikido, heavily reliant on sheer strength and athleticism, tends to deteriorate as one ages. The body inevitably succumbs to the wear and tear of time, rendering such techniques increasingly difficult or even impossible to execute effectively.

My ongoing goal is to unravel the essence of the aikido practiced by Saotome Sensei. Despite nearing ninety, he remains as proficient on the mat as ever. Witnessing his prowess firsthand is truly remarkable. At our aikido summer camp last year, I watched as Sensei effortlessly handled practitioners much younger and physically imposing than himself. It’s a testament to the power of authentic aiki, transcending mere physicality.

Some of our younger practitioners still push themselves to the limits during training sessions, a dedication I once shared but have since retired from. Yet, seeing Sensei seamlessly navigate through techniques, unfazed by size or strength differentials, reignites my passion for understanding true aiki. It’s this pursuit of comprehension that continues to drive and motivate me in my aikido journey.

MAYTT: Sounds like it. What challenges have you encountered in bringing up the newer generations in aikido?

GL: I’ve made it a priority to impart my knowledge to my senior students so that when I’m no longer here, they’ll possess enough understanding to carry on. As I approach my early seventies, it’s disheartening to see how many of my peers from the early days are no longer with us. Sensei promoted around seven individuals to seventh dan, and sadly, more than half of them have passed away. It’s a sobering reminder that time is fleeting, and there’s a sense of urgency in passing on what I’ve learned.

I’ve taken steps to ensure that my students are well-prepared for the future. Many of them are ahead of where I was in terms of understanding at the same rank, thanks to efforts in shortening the learning curve. They know what’s required to improve, and I’ve instilled in them the importance of continuous growth. Additionally, I’ve facilitated relationships between my students and esteemed teachers like Bill Gleason Sensei and Howard Popkin Sensei. They’re on a first-name basis, and these connections will serve them well in their ongoing development.

Now, it’s a matter of moving forward steadily. My hope is that my students will continue to progress and uphold the principles and techniques they’ve learned, even in my absence.

My wife and I have recently relocated to Santa Fe, marking the beginning of some significant life changes for us. We’re transitioning into retirement here, and part of this process involves figuring out how to pass my dojo off to my students. The economic landscape for this endeavor is different now compared to the 1980s when I began teaching professionally. Since 1986, I’ve been teaching aikido full-time, and by aikido standards, I may be considered one of the more successful non-Japanese teachers in terms of economic viability.

In the past, I taught seminars across the country and in Europe, and my dojo was profitable. Additionally, I ventured into creating instructional videos, which turned out to be a successful endeavor. Thanks to the Internet, these videos reached practitioners worldwide, with copies sold on every continent except Antarctica. This allowed me to modestly support myself, which is an achievement in the world of aikido, where many instructors struggle to make ends meet.

As I contemplate retirement and the future of my dojo, I’m reflecting on the journey I’ve had as a professional aikido teacher. Despite the challenges, I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished and the impact I’ve had on students around the globe through my teaching and instructional materials.

Unfortunately, the current landscape doesn’t allow for the same economic viability as before. The rent for my dojo has risen to the point where it’s barely breaking even. Additionally, the aftermath of Covid-19 has led to the closure of many of the places where I used to teach seminars annually. Others have become so small that they can no longer accommodate seminars. This decline in opportunities has also affected my video business, as there are fewer people purchasing instructional videos nowadays.

Reflecting on my generation of aikido practitioners, many of us found ourselves running dojos at the sandan level. This was largely due to the lack of senior instructors in our areas. Unless you were in a major hub like California or New York, there weren’t many higher-ranked practitioners to learn from. Consequently, we took on the responsibility of opening and running dojos, some of us as professional instructors and others as amateurs.

To transition to the next phase, it’s essential to recognize the shifting landscape of aikido today. Unlike before, there’s now an abundance of senior practitioners and numerous dojos in operation. In the Seattle Metro area alone, there were over twenty dojos before the lockdown – an exponential increase from when I started, with just four. This proliferation has diluted the student base across multiple dojos, making it challenging for any one dojo to thrive. Despite this, I’m fortunate to have dedicated senior students, some fifth dans with over twenty-five years of experience, who are fully capable of upholding the quality of instruction.

Looking ahead, the future of my dojo hinges on someone stepping up to take on the responsibility. With my lease set to expire in two years, and my own age advancing, I’m not in a position to renew it at seventy-four. The decision to pass on the dojo to a new generation is both necessary and bittersweet. While it’s difficult to let go, it’s the natural progression. Like Mary Heiny Sensei, I’ll continue sharing my knowledge through seminars, embracing a more nomadic teaching style.

In Santa Fe, where I’ve relocated, there are already two seventh dans, one from Chiba Sensei and another from Ichiro Shibata Sensei. With such senior instructors present, there’s no need for me to establish another dojo in the area. Instead, I’ll remain open to teaching wherever there’s interest, supported by my organization for seminars and events. As I navigate this transition, it’s a time of change and adaptation for me, embracing new opportunities while honoring the legacy of my dojo’s past.

This interview is the first part of a two part interview. Read the second part here.

To learn more about aikido and its history in America, click here.